Once the dominant form of capital return, regular dividends have been in secular decline since the early 1980s. In this post we consider why.

A Safe Harbor for Share Repurchases

At the time of Lintner‘s seminal survey in 1956, dividends were the dominant form of capital distribution. As surplus cash built on the balance sheet, managers revised payouts upwardly (and, conversely, dividends were reduced in downturns.) The stickiness of dividends was noted, as managers approached payout policy making as two linked decisions: first, whether to change the payout level, and second, how large a change to make. Dividend policy discussions focused not on the level of dividend, but rather the amount of change.

A firm’s repurchases of its own common equity, given its access to nonpublic information, might be suspect: assuming managers own shares themselves, these repurchases could be constructed to manipulate the price unfairly. The prospect of charges under the anti-fraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the 1934 Exchange Act limited share repurchase activity for most firms. The decline of dividends began in 1982, when the SEC adopted rule 10b-18, which established a safe harbor for share repurchases when managers specify manner, price, volume, and timing of repurchases in advance.

The impact was immediate. Jagannathan et al. (Financial flexibility and the choice between dividends and stock repurchases, 2000) found that from 1985 to 1996, repurchase program announcements grew 650%, compared to a doubling of dividends over the same period.

Brav et al. updated Lintner’s work by surveying 384 financial executives on payout policy; their 2004 paper is today one of the most widely cited studies in the field. They found that payout decisions are still made conservatively (e.g., dividends are “sticky”), but that payout ratio (fraction of earnings distributed) was no longer the dominant driver of dividend rate decisions: today’s managers target DPS and other measures (such as growth in dividends or dividend yield).

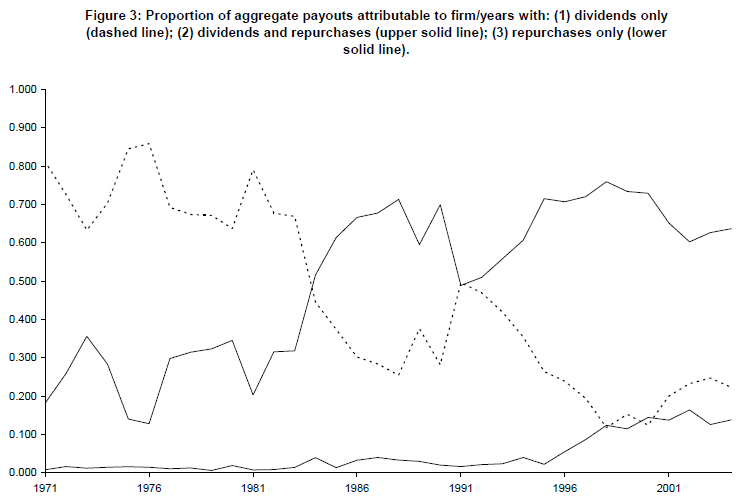

Brav et al. were also able to gather data on share repurchase practices. A plurality of repurchasing firms target the dollar value of distributions, which by itself demonstrates the sea change in capital distribution thinking in the last half century: dividends today represent a relatively stable payout from retained earnings, while share repurchases are the technique of choice for distributing the residual. Skinner (Relation between Earnings Dividends Repurchases Skinner 2006) goes further, noting that the archetypal Lintner-era firm, which distributes capital solely via dividends, has disappeared. Figure 3 from that paper illustrates the point:

Investor Tax Clienteles

The differential tax treatment of dividends vis-a-vis share repurchases has not historically been a large influence on payout policy: management generally sets dividend policy with little regard for investor tax effects. The 2003 dividend tax cut provided an opportunity to demonstrate this fact; Brav et al. in 2008 surveyed the management response. One might have expected an increased use of dividends for capital return; that didn’t occur:

We find that the tax rate reduction increased the likelihood of dividend initiation, but the effect was only second-order important. We also find that the tax cut had a smaller effect on increases in payout by long-time dividend payers. We corroborate these results by showing that firms only occasionally mention the dividend tax rate when publicly explaining why they initiate dividends. Combining these results with the observation that aggregate repurchases have increased more than dividends since the May 2003 tax cut, we conclude that taxes are second-order important in dividend decision…

These results may have important policy implications because the reduction in dividend taxes is scheduled to expire late this decade. Our results suggest that dividend payout will not dramatically decrease if dividend tax rates return to their historic levels. Because retail investors are not perceived to be particularly important investors in stocks, we would not expect corporations to respond dramatically to an increase in the relative tax rates of retail investors.

We should point out that there is strong evidence that some investors (typically, retail, risk-averse, and older) prefer dividend-paying stocks; see for example Kawano (The dividend clientele hypothesis: evidence from the 2003 tax act, 2011), Becker (Local dividend clienteles, 2009), and Graham and Kuman (Do dividend clienteles exist? Evidence on dividend preferences of retail investors, 2006). There is also some evidence (e.g. Desai et al., Institutional tax clienteles and payout policy, 2007) of clienteles among institutional investors, though these preferences work in the opposite way: institutional investors are generally either indifferent or averse to dividends. Reconciling these findings with management and overall market behaviors leads us to suspect that marginal investors do not prefer dividends.

Other investor factors may be at play. For example, Fama and French, seeking in 2001 to explain the disappearance of dividends, noted the lower transactions costs for selling stocks for consumption purposes, in part due to an increased tendency to hold stocks via open-end mutual funds. Where investors desire an income-generating asset, they may cheaply create a synthetic dividend by selling a fraction of their holdings.

Management Prefers Share Repurchases

Among other findings, Brav et al. discovered that managers prefer share repurchases to dividends because the former are more flexible and may afford the company the opportunity to time the equity market or enhance EPS.

Furthermore, managers discount the importance of clientele effects: they believe that institutions (the presumed marginal investors) are indifferent between dividends and repurchases. Other survey findings indicate management views providing little support for agency considerations or signaling effects, and confirm our suspicion that tax considerations are secondary.

Fama and French, in the 2001 study cited above, point to

larger holdings of stock options by managers who prefer capital gains to dividends; and better corporate governance technologies (e.g., more prevalent use of stock options) that lower the benefits of dividends in controlling agency problems between stockholders and managers

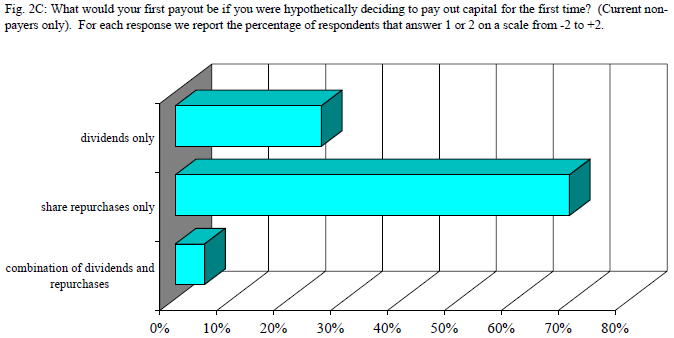

Brav et al. summarize these various considerations with the illuminating response to their question: Would you prefer to distribute via dividends or repurchases? Managers at firms who had yet to initiate either program clearly would prefer repurchases:

The findings were similar among current payers was similar: “Once free of the tradition of paying dividends, most firms would emphasize repurchasing shares. That is, once all constraints are removed, most payers would substitute from dividends towards repurchases.”

Leave a Reply